PRE

Diet is linked to fat loss, muscle growth, and health. These three circles converge more than diverge. The biggest chasm is between fat loss and muscle growth. In the end, however, the chasm is child’s play. There’s only one small difference between dieting for fat loss and dieting for muscle growth.

- Fat loss: supply less energy.

- Muscle growth: supply more energy.

Once the system is set, we can turn the dial in the appropriate direction with ease.

Speaking of ease, I created a calculator that handles the math that follows. You enter your weight and you get an estimate of what you should eat based on your goals. What follows is how the sauce is made. Don’t let the numbers distract you. Focus on the concepts.

If you’re returning to this and want to teleport to the calculator click here. (Not recommended unless you’ve already read through the rationale.)

NOOBTRITION is a first-principles approach to eating for a better body composition.

PRE

The first principles of eating for a better body composition have universal application. Everyone under the sun must obey them.

This is not a diet. This is a list of irreducible principles underpinning every successful body-composition-based diet.

Diets are recipes. They’re specific instructions you’re expected to follow in order to create a specific outcome with a specific set of ingrients.

Diets are littered with particulars.

Particulars should consider your personality and your preferences.

What time should you eat? How many meals should you eat? What specific foods should you eat? The answers to these questions are particulars. They don’t impact the outcome enough to have black-and-white answers. Your personality and your preferences should

Not everything is as negotiable.

The principles of a diet are…

And what did, foundation of NOOBTRITION, is to pull out the first-principles of most successful body-composition based diets.

You don’t second guess what you eat when you’re young. You eat food that you think tastes good. And then, one day, you learn how food affects your body composition. Everything changes. You second guess everything you put into your body.

This is not a diet. Diets are recipes. The list of ingredients is the foods that are acceptable to eat. The are step-by-step instructions are the rules that tell you exactly what you should do with the ingredients

I have nothing against diets. I have my own diet called Two Meal Muscle. My diet is my diet.

NOOBTRITION attempts to tackle that question starting superficial and going granular. This bot a diet so much a collection ofl principles that basis of every successful bcomo based deit. The reason NOOBTRITION not supersoecif bc the nitty gritty of most diets are matter of preference more than matter of truth.

At least as far as

This is the backbone of my diet strategies. There’s no glitter. Just the stuff you need to get the results you want. It’s boring. By design.

PRE

Diet is linked to fat loss, muscle growth, and health. These three circles converge more than diverge. The biggest chasm is between fat loss and muscle growth. In the end, however, the chasm is child’s play. There’s only one small difference between dieting for fat loss and dieting for muscle growth.

- Fat loss: supply less energy.

- Muscle growth: supply more energy.

Once the system is set, we can turn the dial in the appropriate direction with ease.

Speaking of ease, I created a calculator that handles the math that follows. You enter your weight and you get an estimate of what you should eat based on your goals. What follows is how the sauce is made. Don’t let the numbers distract you. Focus on the concepts.

If you’re returning to this and want to teleport to the calculator click here. (Not recommended unless you’ve already read through the rationale.)

5. Symbolize

Transforming numbers into symbols.

Knowing the calorie ceiling and the protein target, you can get a better picture of what you should eat. There are many ways to do this. The “gold standard” leans into math and a nifty algorithm that says: “Eat this many grams of proteins, this many grams of carbohydrates, and this many grams of fats.”

My approach is a little more user-friendly.

At least, I think it is.

First, recall the ceiling.

The calorie ceiling is the anchor.

CUTTING: WEIGH 180 POUNDS x 12 = 2160 CALORIES

BULKING: WEIGH 180 POUNDS x 15 = 2700 CALORIES

The energetic consequence of your target protein intake falls under the umbrella of this calorie ceiling. One gram of protein “contains” four calories. (Granted, I have beef with this standard and I question how much energetic material proteins actually yield, but best practice says you should consider the energetic component of proteins.)

Second, calculate the energetic component of your target protein intake.

Take your weight, which is your target protein intake in grams, and multiply it by four.

EXAMPLE: WEIGH 180 POUNDS x 4 = 720 CALORIES

This represents the minimum energetic impact of your protein intake. As mentioned, foods that contain proteins usually contain either carbs and/or fats, so the actual energetic impact of your protein intake will be larger. We will deal with this soon. For now, roll with the minimum.

Third, find your “remainder” energy intake.

Subtract the minimum energetic impact of your protein intake from your calorie ceiling. This yields your remainder energy intake, to be split between carbohydrates and fats.

CUTTING: 2160-720= 1440 CALORIES

BULKING: 2700-720= 1980 CALORIES

I don’t play favorites. Eating a mixture of carbohydrates and fats is best, and a 50/50 split is a fine place to start. Ultimately, the only thing that matters is respecting the ceiling. Carbohydrates and fats are alternating pistons. Both can be in the middle, but when one is high, the other one better be low.

Fourth, set the symbols.

We could translate the remainder-energy-intake ceiling into more specific targets: grams of carbohydrates and grams of fats. I don’t. I like thinking about:

- Grams of proteins.

- Calories of “remainder” energy.

Instead of turning your remainder energy intake into grams of specific macronutrients, I break it into 100-calorie chunks which are symbolized by one ⚡ lightning bolt.

1440 CALORIES would be roughly 14 bolts.

1980 CALORIES would be roughly 20 bolts.

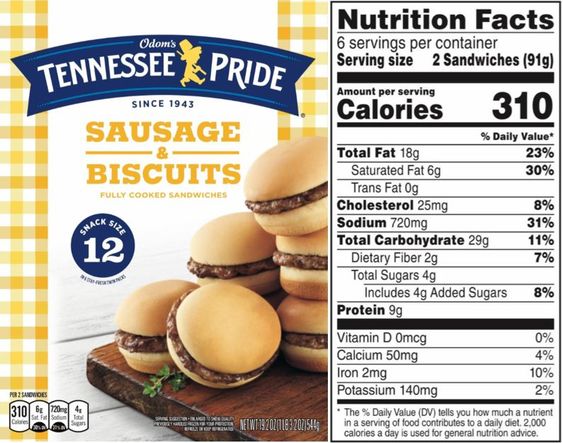

Think of a banana. In general, bananas contain 100 calories. Boom. There’s one ⚡. Making oatmeal? The nutrition facts say one cup contains 300 calories. You make one cup. Boom. There are three ⚡⚡⚡. Putting cheese on your eggs? Thanks to Google, you know 1 ounce of cheddar cheese contains a little over 100 calories. Also, you never realized cheese contained so many calories, which is why you put 500 calories worth of cheese on your eggs. Boom. There are five ⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡.

I find working with ⚡ and thinking of my carbohydrate and fat intake in 100-calorie chunks to be insanely user-friendly.

Proteins get broken into 25-gram chunks, symbolized by a 🥩 steak.

180 GRAMS OF PROTEINS would be roughly 7 steaks.

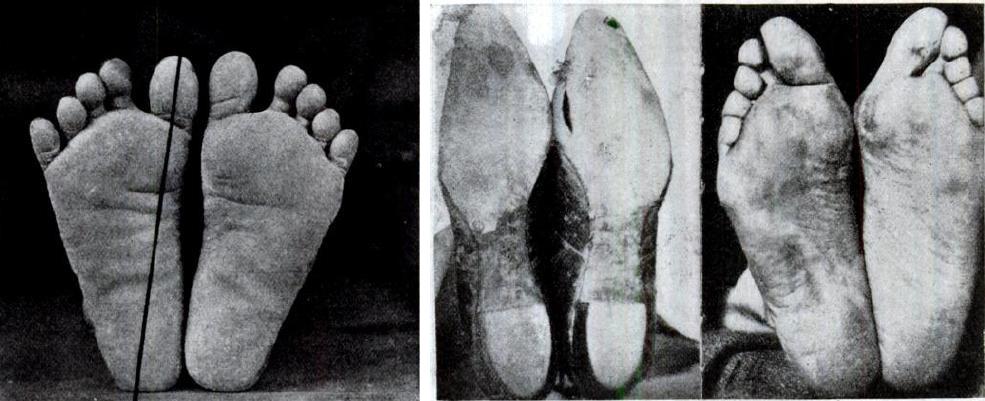

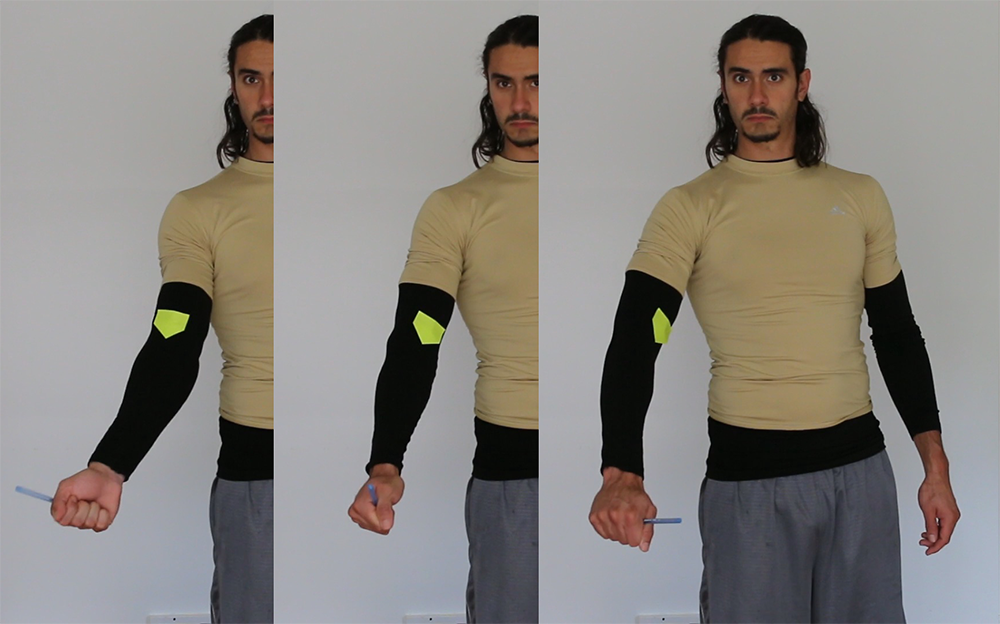

In general, a hockey-puck-sized portion of protein-rich foods contains around 25 grams of proteins. (Think about a can of tuna — that’s the size.) This shortcut only applies to protein-rich foods.

Protein-rich foods’ macronutrient distribution skews toward protein, and there are two different categories of protein-rich foods.

First, lean proteins.

Lean proteins contain mostly proteins; their macronutrient distributions are heavily skewed in favor of protein.

Here are examples of lean proteins: chicken breast, beef liver, tuna, turkey breast, buffalo, elk, mahi-mahi, pork tenderloin, venison, scallops, shrimp, 90/10 (or higher) ground beef, greek yogurt, sardines, etc…

I discard the minuscule energetic component of lean proteins and symbolize a hockey-puck-sized portion of them with one meat symbol.

🥩 = 25 grams of lean proteins

Second, chubby proteins.

Chubby proteins contain a decent amount of protein alongside a decent amount of energetic material; their macronutrient distributions are split (somewhat) in half between proteins and carbs/fats.

Here are examples of chubby proteins: pulled pork, turkey legs and thighs, chicken legs and thighs, cottage cheese, salmon, most unflavored and unsweetened yogurts, eggs…

Because of their energetic burden, a hockey-puck-sized portion of chubby proteins get symbolized with one meat symbol and one lightning bolt.

🥩 = 25 grams of lean proteins

⚡ = 100 calories of energy

There exists a third category of proteins called purgatory proteins, which contain a small number of proteins alongside a higher amount of energetic material; their macronutrient distributions are skewed against protein.

Examples of purgatory proteins: black beans, almonds, peanut butter, sausage, milk, most cheeses

Although the proteins in these foods “count,” they usually contain too much energetic material to be relied on for the bulk of your protein intake under “normal” circumstances. If you’re a vegan and you don’t eat meat, you have to rely on purgatory proteins, which will restrict your food choices. You’ll have to make sure the carbohydrate- and fat-dominant foods you eat also contain some semblance of proteins.

Fifth, symbols to foods.

Now we need to turn the symbols into specific foods and meals, which is something I refer to as “diet design.”

This isn’t an exact science. Your personality and preferences are important.

1. General principles:

First, frequency.

Not long ago, everyone thought eating frequent small meals increased metabolism, leading to better fat loss. This has been debunked. The quantity of food consumed across the day matters more than how often you eat. In other words, it doesn’t matter how often you eat… for fat loss.

For muscle growth, there’s some evidence suggesting 3-4 meals might be ideal as long as…

Second, proteins.

Protein should be at the center of every feeding and you should split your protein intake somewhat evenly across your meals.

The reason 3-4 meals might be ideal as long as they’re centered around proteins

goes back to the old adage about the body only being able to use a certain amount of proteins in a certain period of time.

by “pulsing” you give body enough, not too much, then later, more receptive.

However, most research in this area is done with protein supplements, which have a notoriously fast absorption rate.

Whole-food proteins take longer to digest, especially when mixed with other foods. Also, certain factors influence how many proteins your body can use in a certain period of time. For instance, your body might be more receptive to a surge of proteins after a muscle-based training session or after a period of fasting.

Personally, I haven’t eaten more than two meals per day since 2011. And during the most muscularly-prosperous time of my life, I was only eating one meal per day. (Of course, there’s no way to know if I would have gained more muscle if I was eating more often.)

If you want to live and die by the (somewhat qestionable) science, eat 3-4 meals and split your protein intake evenly across those meals.

I say, for starters, eat however many meals you want as long as you eat respectable portion of proteins every meal. Far more important than meal freq is…

Third, consistency.

Select a meal frequency and schedule you can see yourself sticking to. For instance, as mentioned I eat two. If love breakfast then elim, too much resistance.

in the end, structure you want to settle into eating same number of meals daily and eating those meals at the same time.

Your body will regulate hunger and appetite around your schedule. If you eat breakfast every day at nine o’clock, you’ll be hungry (or, at least, you’ll want to eat) every day at nine o’clock.

Avoid unplanned feedings. Eat when you’re supposed to eat. Don’t eat when you aren’t supposed to eat. Snacking shouldn’t be impulsive. If you like to snack, it should be accounted for ahead of time.

–

peri-workout nutrition.

overblown.

My ideas:

composition.

In general, each meal should have [1] at least one protein-dense food, [2] some plant carbs and/or fruit, and [3] an appropriate portion of energy carbs or fats.

Fifth, boring.

Eating the same meals every day makes life easier. You’ll know what to buy at the supermarket every week. You’ll learn how to prepare and cook your meals in a time-efficient matter. Everything becomes more habitual, and thus easier. If you need variety in your diet, I suggest making one meal a misfit meal. In other words, eat the same breakfast daily and the same lunch daily, but vary your dinners every day.

but before we do we need to talk logistics.

First, meal frequency doesn’t really matter.

Here are things that should sway:

First, when do you enjoy eating?

Second, consistency.

More important than how many meals you eat is having a schedule and being consistent.

Transforming these symbols into

2. Personal particulars:

First, foods.

Identify foods you can afford and can see yourself eating regularly within each core category. Here are my foods:

Proteins: chicken breasts, chicken thighs, ground beef and muscle meats, organ meats (specifically liver and heart), salmon, sardines, eggs, Greek yogurt, cottage cheese, kefir, and milk.

Energy carbs: raw honey, fruits, potatoes, and rice.

Plant carbs: cabbage, sauerkraut, carrots, broccoli, onions, Brussels sprouts, and asparagus.

Fats: cheeses, olive oil, butter, and peanut butter.

Your list should look different. My list looks different every year. I wasn’t eating liver or sardines a few months ago. I couldn’t stomach them. I learned to like them because of their health benefits.

Eat what you can eat.

Second, meals.

Combine the foods from the exercise above into appetizing meals. Of course, “appetizing” is subjective. I eat sardines and sauerkraut for lunch. I don’t expect you to do the same. Remember the template:

- Protein-dense food

- Plant carbs and/or fruit

- Sane portion of energy carbs or fats

Be sure to consider the logistics of each meal. For instance, if you don’t have time to cook in the morning, don’t plan on eating steak and eggs. Or if you eat lunch in a crowded break room, don’t plan on eating loud-smelling tuna.

3. Sloppy specifics:

I can’t create meals for you, but I can give you an example of what all of this might look like atop three square meals.

Assume a weight of 180 pounds:

🥩🥩🥩🥩🥩🥩🥩

⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡

♾️🥦

Breakfast

Six eggs 🥩🥩⚡⚡

Banana (or other fruit) ⚡

Kefir 🥩⚡

Lunch

Sardines (or chicken breast) 🥩

Apple (or other fruit) ⚡

Carrots (or other plant carb) 🥦

Dinner

Ground beef 🥩🥩⚡⚡

Steamed broccoli (or other plant carb) 🥦

Small bowl of rice (or other energy carb) ⚡

Cottage cheese 🥩🥩⚡⚡

Blueberries ⚡

For variety, you can keep the template intact and change some of the foods. For instance, for dinner:

Salmon 🥩🥩⚡⚡

Steamed broccoli (or other plant carb) 🥦

Baked potato (or other energy carb) ⚡

Cottage cheese 🥩🥩⚡⚡

Blueberries ⚡

There are many ways you can move things around to better suit your personality. For instance, I like eating a bigger dinner. I’d opt for leaner proteins at breakfast (instead of eggs), which would give me more energetic freedom at the dinner table.

In the end, this matters most:

🥩🥩🥩🥩🥩🥩🥩

⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡

♾️🥦

How you put it into play should pander to your preferences and your personality.

, important to settle some logistics matters.

First, meal frequency doesn’t really matter. Not long ago, boost metabolism, no. For fat loss, quantity matters more.

Now, there’s some nuance here b/c if you ate all before bed, tummy upset.

some evidence suggesting for muscle growth, maybe better off spreading and putting protein. LEUCINE THRESHOLD

in general, just say, doesn’t matter how many, just make proteins center and, in general, should consist of something else, too. protein shake not really “meal.”

w/ this, here things to consider.

first, convenience.

second, consistency.

third, post workouts?

Few people like hearing this but best to know what and when and to stick with the plan. Spontaneity is enemy. Routine helps. Helps everything from…

This isn’t to say eat same things. Helps, but not difficult to create meals for each day that hit. Point being

CUTTING:

180 GRAMS OF PROTEINS

🥩🥩🥩🥩🥩🥩🥩

1440 CALORIES OF ENERGY

⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡

BULKING:

180 GRAMS OF PROTEINS

🥩🥩🥩🥩🥩🥩🥩

1980 CALORIES OF ENERGY

⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡

5. Logistics

Before we talk about specific foods, important to settle some logistics matters.

First, meal frequency doesn’t really matter. Not long ago, boost metabolism, no. For fat loss, quantity matters more.

Now, there’s some nuance here b/c if you ate all before bed, tummy upset.

some evidence suggesting for muscle growth, maybe better off spreading and putting protein. LEUCINE THRESHOLD

in general, just say, doesn’t matter how many, just make proteins center and, in general, should consist of something else, too. protein shake not really “meal.”

w/ this, here things to consider.

first, convenience.

second, consistency.

third, post workouts?

8. Picture

Turning symbols into foods

From here, we have a nice drag-and-drop framework to work with. The only difference between cutting and bulking is the amount of remainder energetic material.

CUTTING:

180 GRAMS OF PROTEINS

🥩🥩🥩🥩🥩🥩🥩

1440 CALORIES OF ENERGY

⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡

BULKING:

180 GRAMS OF PROTEINS

🥩🥩🥩🥩🥩🥩🥩

1980 CALORIES OF ENERGY

⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡⚡

cramming into however many meals you decide to eat and then applying specific foods.

tips?

This something you have to do for yourself.

For instance, I eat

–

how to put into day? well, depends on personality. and prerefences. from afar, matters most. to see how i use, two meal muscle.

Here are some things to consider when selecting specific foods to eat to reach this protein quota:

What foods do you enjoy eating? You won’t get very far if you’re eating foods you hate every meal. Of course, extending beyond your comfort zone for health purposes isn’t a bad thing (eat liver!), but you should look forward to eating most of your meals.

What foods can you afford? You don’t have to eat steak every meal. I eat sardines every day for lunch. They are cheap. (But not as cheap as canned tuna.)

What foods are convenient and match the mood of your meals? Does your lunch need to be handheld? Portable?

What’s the nutrient yield? Canned tuna is cheaper than sardines, but sardines are 10x healthier. Beef liver is nature’s multivitamin. Grass-fed beef is chock full of good stuff.

What’s the energetic consequence? Unfortunately, proteins aren’t foods. Foods that contain protein

select number of meals. spread proteins somewhat evenly.

5. Algorithm

Knowing the calorie ceiling and the protein target, a nifty algorithm arises to help us solve the remainder of the puzzle. Luckily, computers can work through algorithms with ease. What follows is how the sauce is made. Afterward, there’s a calculator that will do all of this math for you.

1. CALORIE CEILING

Find your calorie ceiling by multiplying your weight by twelve for fat loss or by fifteen for muscle growth.

BWx12 = CUT

BWx15 = BULK

I weigh 180 pounds, therefore my calorie ceiling for fat loss is 2160 calories. For muscle growth, it’s X

2. PROTEIN TARGET

Multiply your weight by one.

BWx1

I weigh 180 pounds, therefore my target protein intake is 180 grams, regardless of my goal.

3. PROTEIN’S IMPACT

Calculate the minimum caloric impact of your protein intake by multiplying your protein target by four.

(BWx1)x4

My target protein intake is 180 grams, therefore the minimum caloric impact of my protein intake is 720 calories. This is labeled “minimum caloric impact” because macronutrients are foods. Foods contain proteins, but they also contain carbs and/or fats.

And so, as a consequence of reaching your protein quota with real foods, you will most certainly consume more than 720 calories. This is okay. Just calculate the minimum for now.

4. REMAINDER CALORIES

After factoring out the minimum caloric impact of your target protein intake, delegate the remainder of calories evenly between carbs and fats.

CALORIE CEILING – PROTEIN CALORIES

My calorie ceiling is 2160 calories and the minimum caloric impact of my protein intake is 720 calories. This means I have 1440 calories remaining to be split equally across carbs and fats. This means 720 calories go toward carbs and 720 calories go toward fats.

NOTE:

Wars have been waged over both of these macronutrients. Not long ago, fats were demonized. CHOLESTEROL KILLS! EGGS ARE BAD FOR YOU! FAT MAKES YOU, UHHH, FAT? Energy carbs have also walked the plank. INSULIN IS EVIL! ANTI-NUTRIENTS! FRUIT IS SUGAR! YOU DON’T NEED CARBS TO SURVIVE!

Eh.

The Okinawans eat mostly carbs, specifically potatoes. They have one of the longest reported life spans of any culture and they aren’t nearly as fat as carbohydrate-conscious First World goobers. The Inuits eat mostly fat, specifically whale blubber. They rarely ever get heart disease.

I don’t have the audacity (stupidity?) to condemn energy carbs or fats without valid medical reasons. (If your throat swells up and you almost die when you eat bread, then, yeah, maybe you shouldn’t eat carbs.) Both energy carbs and fats are useful.

Fats are essential, meaning we need them to survive, yet we can’t produce them ourselves.

FAV FATS?

Granted, fats have over twice the energy as an equivalent amount of carbs. It’s easy to overeat fats, which is why I can’t be within a ten-foot radius of pistachios. This doesn’t make them “evil,” though.

The primary argument against carbs is that they are non-essential, meaning we don’t need them to survive. True. But this doesn’t mean they’re dangerous. In the late 1930s, Dr. Walter Kempner put his patients (many had high blood pressure and kidney issues) on a strict diet consisting mostly of white rice, fruit, juices, and sugar. In one study of 106 patients, everyone lost at least 99 pounds.

FAV CARBS; FRUITS, POTATOES; HONEY

Beyond recognizing different foods have different nutrients, when it comes to carbohydrates and fats, the most important thing is keeping overall energy intake aligned with your goal.

For starters, I delegate the remainder of calories across carbs and fats equally, 50/50, but you can distribute them however you want as long as you respect your ceiling.

5. CALORIES TO GRAMS

Turn the caloric allotment for carbs and fats into grams. There are four calories in one gram of carbohydrate. There are nine calories in one gram of fat.

CARBS CALS / 4

FAT CALS / 4

I can eat 720 calories of carbs, which equates to 180 grams of carbs. I can eat 720 calories of fats, which equates to 80 grams of fats.

6. SYNTHESIZE

ENERGY CEILING: 2160 CALORIES

PROTEIN TARGET: 180 GRAMS

CARB ALLOTMENT: 180 GRAMS

FAT ALLOTMENT: 80 GRAMS

7. AUTOPILOT

Getting these numbers is so easy the computer can do it for us:

CALCULATOR ~

The difficult part is turning these numbers into foods and meals.

Pick proteins wisely.

pro plays center and so important to pick. beyond enjoyment, “other.” macros aren’t foods and so baggage…

Increasing your protein is a bit more complicated than “eating more proteins” because many foods that contain proteins also contain carbs and/or fats. As long as you’re eating Mother Nature’s foods there’s nothing inherently negative about carbs and/or fats attached to proteins, however, overall energy intake is the dial determining the direction of your diet.

- More energy = muscle-growth focused

- Less energy = fat-loss focused

And so, “secondary” energy accompanying protein sources can’t be ignored, especially if you’re trying to lose fat. For instance, wellness websites (with pastel color schemes) often list peanut butter as a good source of proteins, but the overwhelming majority of peanut butter isn’t protein.

Here are the specific nutrition facts, according to Google, per one serving (two tablespoons):

Fat: 16 grams

Carbs: 6 grams

Protein: 8 grams

In order to get 100 grams of proteins via peanut butter, you’d have to eat around 12 servings, which would also amass 192 grams of fat and 2256 total calories.

Peanut butter contains protein, but it’s not a protein-dense food. Relying on peanut butter for a large portion of your protein intake will amass a bunch of extra energetic material. Usually not good.

In order to better navigate “secondary” energy accompanying protein sources, we can crack proteins into three different categories:

Lean proteins.

Foods that contain mostly proteins are lean proteins.

Here are examples of lean proteins: white meat chicken breast, tuna, lean turkey (breast), buffalo, elk, mahi-mahi, pork tenderloin, venison, scallops, shrimp, 90% lean or higher beef, unsweetened and unflavored Greek yogurt, etc…

Look at chicken breast:

- Serving: 3 oz

- Calories: 128

- Proteins: 26 g

- Fats: 2.7 g

- Carbs: 0 g

Chubby proteins.

Foods with a decent amount of proteins alongside a decent amount of energetic material are chubby proteins.

Here are examples of chubby proteins: pulled pork, dark meat turkey, cottage cheese, dark meat chicken, sardines, salmon, unsweetened and unflavored yogurt, eggs…

Look at cottage cheese:

- Serving: one cup (225 g)

- Calories: 222

- Proteins: 25 g

- Fats: 10 g

- Carbs: 8 g

Purgatory proteins.

Foods that contain a small number of proteins alongside a decent amount of energetic material are purgatory proteins.

Here are examples of purgatory proteins: milk, kefir, cheese, nuts (peanuts, almonds, pistachios), seeds (sunflower, chia, flax), grains…

Look at almonds:

- Serving: 1/4 cup

- Calories: 170

- Proteins: 6 g

- Fats: 15 g

- Carbs: 5 g

Categorizing protein-containing foods in relation to their accompanying energetic material is useful, especially when you’re trying to keep your protein intake high and energy intake low (ideal for fat loss). Even when you’re bulking and you have more energetic leeway, you don’t have infinite leeway; you need to keep an eye on your energy intake. In general, no matter your goal, lean and chubby proteins will anchor your protein intake.

ultimately pro matters most, but ..

fat loss; lean toward lean

muscle growth; little more lax…

this just general rule and preference. could fully eat lb fatty ground meat and chill if down. imo, more variety and in order to have leeway, leans important

Choose carbs with care.

w/ pro, have idea that macros really not great, and can also see w/ carbs. subset of carbs

The foods usually associated with “carbohydrates” are what I refer to as energy carbs.

ENERGY CARBS

Energy carbs contain higher levels of starch and sugar.

Examples of energy carbs: potatoes, oats, rice, grains, pasta, bread, flour-based products, corn, fruits (apples, bananas, oranges, lemons, limes, kiwis, grapefruits, kumquats, pears, pineapples, grapes…), berries (blueberries, raspberries…)…

Look at potatoes:

-

- Serving: 200 grams

- Calories: 154

- Proteins: 4 g

- Fats: 0 g

- Carbs: 34 g

PLANT CARBS

Plant carbs contain lower levels of starch and sugar.

Examples of plant carbs: broccoli, cauliflower, carrots, cabbage, lettuce, tomatoes, peppers, celery, eggplant, onions, asparagus, sprouts, lettuce, mushrooms, spinach, zucchini…

Look at broccoli:

-

- Serving: 200 grams

- Calories: 68

- Proteins: 5 g

- Fats: 0 g

- Carbs: 14 g

Plant carbs are complex fibrous foods with a skewed volume-to-energy ratio. They don’t contain much energetic material. For instance, you can eat three times the amount of broccoli (in volume) as you can potatoes, for the same caloric yield.

- 200 g raw broccoli = 68 cals.

- 200 g red potatoes = 178 cals.

Factoring out fiber (5 grams), 200 grams of broccoli contains closer to 50 calories. (Fiber is a type of carbohydrate your body can’t digest, which means it doesn’t yield energetic material.)

Given the opportunity to eat unlimited broccoli, you’ll probably hit a point of fullness (or boredom) before you’re able to amass a bunch of energetic material. Most plant carbs follow the same trend. This isn’t to say the energy in broccoli (or other plant carbs) doesn’t “count.” It does. But, in general, because of their volume-energy-fiber ratio, you can eat a lot of them without worrying about amassing excess energetic material.

Drink ….

==

As a crude estimation, one hockey-puck-sized portion of lean proteins and chubby proteins contains around 20-30 grams of protein. (Think: 5-ounce can of tuna.) Using this shortcode, you can estimate what your real-food protein intake should look like.

I weigh 205 pounds, so I need to eat around 7-10 hockey pucks of protein-dense food every day. Let’s make this a bit more tangible:

🥩🥩🥩🥩🥩🥩🥩🥩🥩🥩

Each hunk of meat represents around 20-30 grams of protein-dense food. (Some of these foods may have accompanying energetic material. We will deal with this later.)

My favorite sources of proteins are chicken breasts, chicken thighs, ground beef and muscle meats, organ meats (specifically liver and heart), salmon, sardines, eggs, Greek yogurt, cottage cheese, kefir, and milk.

Contrary to popular belief, meats and protein-dense foods are some of the healthiest foods in the world. Liver is nature’s multivitamin. I eat 1-3 ounces of liver almost every day. (Liver is so nutrient-dense, you don’t have to eat much; eating too much liver might result in overconsumption of certain nutrients and minerals, especially if you’re taking supplements.) Sardines are a great source of omega-3 fatty acids and they aren’t contaminated with metals like other canned fish. Kefir is great for your gut health.

Fourth, pattern.

Center your meals around proteins; spread your protein intake somewhat evenly across your meals.

Much more important than meal frequency is meal patterning. Create a feeding schedule and don’t deviate unless absolutely necessary. Avoid snacking and unplanned eating.

Eat breakfast at the same time. Eat lunch at the same time. Eat dinner at the same time.

body will regulate hunger appetite, everything around schedule. really helps to have one and stick. more chaotic, tough.

MAKE A LIST OF PROTEIN-RICH FOODS YOU CAN SEE YOURSELF EATING AT EVERY MEAL.

NUMBER, ENERGY.

THERE ARE TWO WAYS TO REGULATE ENERGY:

THERE’S A LAZY WAY AND THERE’S A ____ WAY.

GONNA GO B/C I FIND USEFUL AND

—

As mentioned (many times), we derive energetic material from the three macronutrients (proteins, carbohydrates, and fats. Here are the standards:

- Fats: 9 calories per gram

- Proteins: 4 calories per gram

- Carbohydrates: 4 calories per gram

Based on the calorie-per-gram breakdown of each macronutrient, you’d be inclined to say proteins and carbs contain less energy; they have less than half the energy of fats.

You’d be right.

You’d also be wrong.

The macronutrients’ calorie-per-gram standards are somewhat misleading. For instance, they don’t account for the thermic effect of food: Your body uses energy to digest food (digestion is like exercise for your intestines). And different foods and substances require different amounts of energy to break down and process. For example, you need more energy to digest and absorb proteins as compared to both carbs and fats.

- Proteins cost 20-30% of their calories

- Carbs cost 5-6% of their calories

- Fats cost 3% of their calories

In other words, if you eat 100 calories of carbs, you’ll have 95 calories of energetic material leftover to use, whereas if you eat 100 calories of proteins, you’ll only have 70-80 calories of energetic material leftover to use.

Fats and carbs yield more energetic material than proteins, even when eaten in the same (exterior) caloric quantity.

Adding to this, your body doesn’t really like to use proteins for energetic material. (I’ll try keep this explanation brief.) Your body and brain have two primary energy-recycling substances. First, glucose, which comes from broken-down carbohydrates. Second, triglycerides, which come from dietary fat and potentially carbohydrates. (When glucose storage facilities are full, your body will transform free-floating glucose into a fatty acid for storage. Your body can store waaaayyyy more fat than glucose.)

In order to use proteins as energy-recycling substances, your body has to convert them to either glucose (carbs) or triglycerides (fats). Your body only does this when absolutely necessary.

I’m not dumb enough (or smart enough?) to say proteins can’t or won’t be used for energy-recycling purposes. However, don’t think it’s a stretch to say accumulating energetic material is more difficult when eating proteins (specifically lean proteins) as opposed to carbohydrates or fats… unless the type of carbohydrates in question are plant carbohydrates.

—

HEADLINE

Lean proteins and plant carbs are lower-energy foods. Chubby proteins, purgatory proteins, energy carbs, and fats are higher-energy foods.

Higher-energy foods aren’t inherently unhealthy.

=====================

The gold standard for keeping tabs on energy intake is keeping a tally of what you eat. generally, best results use this in conjunction w/ lazy.

calculating, then weighing and measuring.

algorithm stays the same, only major diff is calorie ceiling.

FOR FAT LOSS want conservative deficit, which set your body’s weight (in pounds) by twelve. Low enough to facilitate fat loss, high enough to keep you nourished (assuming you eat nourishing foods). You should lose at least one pound per week. If you weigh 180 pounds, your calorie ceiling is 2160 calories. Generally lose around 1 pound per week. Perhaps more in early thank to fluid, but long run average.

FOR MUSCLE GROWTH want conservative surplus, which much trickier. Generally start at 15-16.

generally gain around 2 pounds per month. gaining more, most likely getting fat. this is a tricky line to walk b/c bw can fluctuate by pounds, so one of those things might have to get adjusted. aka, if start and one month sam average, maybe increase tiny. if you start and 4-5, maybe decrease slightly.

w/ celing set, remainder of algo stays the same. one gram, and c/f split as long as ceiling, okay.

FAT LOSS CALCULATOR

Notes

One gram of pro: symbol. Each repreents 20-30, hockey puck sized portion.

non-starchy, unlimited. toggle the other if nnot working

energy; in form of starchy sugary or fats OR CHUBBY.

if any previous MEAT SYMBOL is chubby, attach bolt. once that, have remainer which can split between or however you prefer. each bolt represents about 100 cals.

MUSCLE GROWTH CALCULATOR

Notes

NEXT PART: TRANSFO

NEXT PART: Q & A

STRATEGY (LAST CATEGORY) CUT FOR EXTENDED PERIODS, THEN BULK… OR ALTERNATE.

Fat loss: less

Muscle growth: more

Thus far, we’ve established a crude system for each direction.

No matter what:

- Stay hydrated

- Eat Mother Nature’s foods

- Eat plenty of proteins

For fat loss:

Rely on lean proteins and plant carbohydrates. Be measured with chubby proteins, purgatory proteins, energy carbs, and fats (eat some, don’t go overboard).

For muscle growth:

alas, a bit too vague. b/c reality is less, but not too much. and on flip side, more but not too more. best w/ narrow window and best to put more precise numbers.

zoomed in.

center each feeding around proteins and either plant carbs or fruits. eat a hockey-puck-sized portion of proteins and a baseball-sized portion of either plant carbs or fruits. eat energy carbs and fats with meals as desired. eat until satiated. don’t eat until stuffed.

still not losing fat?

first, eliminate some of the non-lean proteins, fats, and energy carbs (fruit should be the last energy carb eliminated). use only one bun for sandwiches. fry eggs in less butter. making a few small changes like this every meal will shrink energy supply.

second, substitute foods with lean proteins and energy carbs. substitution is easier than elimination. this is why people trying to quit smoking find something else to do instead of smoke (eat pretzels).

Eating pulled pork?

Replace it with pork tenderloin.

Eating red meat?

Replace it with turkey or chicken.

Eating rice?

Replace half your serving with broccoli.

easy.

Haley Joel Osment saw dead people. i see energy.

- lean proteins 🥩: not energy

- plant carbs 🥦: not energy

- chubby proteins ⚡: energy

- fats & energy carbs ⚡: energy

you can use this heuristic to decode what you eat, to see how much energy you’re eating, and thus how likely you are to gain or lose fat.

cereal with milk for breakfast?

cereal = ⚡

milk = ⚡

turkey sandwich and chips for lunch?

bread = ⚡

mayo = ⚡

turkey = 🥩

chips = ⚡

with this, if you want to bias your diet toward fat loss, you can either eliminate some energy-dense foods or replace them with lean proteins and plant carbs.

problem.

with lazy fat loss, it’s easy to undereat. undereating can trigger undesirable metabolic adaptations. you have been warned. i am absolved of liability. this is my approach. i am not recommending this approach.

reality.

at some point, you’ll probably need to keep an eye on everything you put into your body.

Aligning nutrients to muscle growth (by eating one gram of proteins per one pound of weight) has an energetic consequence.

assuming 205, 205 grams would yield x cals at minimum. in reality b/c foods aren’t macros and most prots have other, would give more.

however, these “standards” are somewhat misleading.

considering proteins set at one gram, accomplishing automatically increases b/c proteins have cals.

–

as u can see, meat and dairy. if by chance ur against… (more later, q and a)

LEAN, CHUBBY, PURGATORY

Thirst is different than hunger. Hunger is an itch for energy and nutrients. Thirst is an itch for liquids and hydration. There’s some overlap between these two sensations, but there’s a reason we have them both.

We thirst for liquids (and not solids) because liquids do a better job of hydrating us.

Imagine putting your favorite meal into a blender and drinking the resultant liquid. Not the same experience. Drinking things is different than eating things.

Liquids bypass our satiety circuitry. We don’t treat them the way we treat solid foods, which is a problem. Do your best to reverse-engineer liquids into solid foods and treat them equally.

Put your favorite meal in a blender

Ultra-low-calorie beverages like black coffee and tea are fine. Sparkling water is also fine (avoid plastic bottles if you can). As with foods, low-processed liquids are better than high-processed liquids. Milk and kefir are 10x better than sugar-soaked sodas.

If you’re addicted to sugar-soaked sodas, ween yourself from them with sugar-free sodas. Studies show artificial sweeteners aren’t the wretched hive of scum and villainy people once thought they were. (Don’t get me wrong, you’re better off without artificial sweeteners in your diet, but, at the same time, it’s probably better to drink sugar-free sodas as opposed to sugar-full sodas. Especially if you’re trying to lose fat.)

You can drink calorie-containing beverages as long as you reverse-engineer them into solid foods and are mindful of quality.

Even if you account for the energy inside of sugar-soaked sodas, they still aren’t good for you.

Sugar-soaked sodas aren’t good.

As mentioned, the big difference between muscle growth and fat loss is energy. For fat loss, need less energy. For muscle growth, generally accepted do better at or slightly above. Bioenergetics of this in B Comp Basics, won’t rehash here. Within the confines of this system, means diff between comes down to energy. everything else stays the same.

explain… gold standard is calculating, then weighing and measuring. i find bridge the gap useful…

FAT LOSS:

TABLE

Algorithm:

Bodyweight in pounds multiplied by 12. This creates a conservative calorie deficit (usually).

Goal to lose around one pound.

Bodyweight in pounds multiplied by 15. This maintance perhaps conservative cal surplus.

One gram of pro: symbol. Each repreents 20-30, hockey puck sized portion.

non-starchy, unlimited. toggle the other if nnot working

energy; in form of starchy sugary or fats OR CHUBBY.

if any previous MEAT SYMBOL is chubby, attach bolt. once that, have remainer which can split between or however you prefer. each bolt represents about 100 cals.

RECOMMENDED:

meal patterning; as mentioned whatever meals. if muscle, perhaps 3-4. more than anything, meal patterning. eat same times daily and have a routine. help w hunger and expectations.

Put into meals?

Deficit across week vs. daily?

TROUBLESHOOSTING?

NUMBER, MUSCLE

much debate over muscle. old school bulk, more and more slight surplus, 200.

VANILLA STRATEGY:

Fat loss until solid.

Slight surplus for muscle, gain slow, until six-pack abs fade.

Return

Underneath the umbrella of Mother Nature’s food, there are certain foods that contain more energy and certain foods that contain less energy. Based on the calories-per-gram breakdown of each macronutrient, you’d be inclined to say proteins and carbs contain less energy; they have less than half the energy as fats.

You’d be right.

You’d also be wrong.

Overt calorie yield doesn’t tell the whole story. For instance, the chemical soup leftover after your body digests proteins isn’t ideal energy recycling material. Your body can and will use the broken bits and bytes for energy when necessary, but, when given the choice, your body would rather use carbohydrates and/or fats for energetic purposes.

Proteins also have a higher thermic effect than both carbs and fats, which is to say: proteins require more energy to digest. In other words, fats and carbs yield more calories than proteins, even when eaten in the same (exterior) caloric quantity.

Eating plenty of proteins will help you control your energy intake.

Unfortunately, you can’t eat proteins. Macronutrients aren’t foods. There’s no such thing as “protein.” There are only foods.

Some foods contain proteins. Many of these same foods also contain “other.” Proteins may not be easily converted to body fat, but “other” probably will be. Peanut butter is a great example.

Fiber.

Fiber is a type of carbohydrate your body can’t digest, which means fiber can’t be used for energy-recycling purposes. There are 20 grams of carbs in 1/2 cup of black beans, but 7 of those 20 grams come from fiber. In other words, black beans only have 13 grams of “useable” carbs, which means they don’t yield as many carbs (and thus, calories) as the raw numbers suggest.

(Still, even after accounting for fiber, black beans are still a non-lean protein…)

Carbs.

Since you’re (now) familiar with fiber, this shouldn’t be surprising: not all carbs are equal. When you think of “carbs,” you probably think of starchy-sugary carbs.

Examples of starchy-sugary carbs: potatoes, oats, rice, grains, starches, pasta, bread, flour-based products, corn, apples, bananas, oranges, lemons, limes, kiwis, grapefruits, kumquats, berries, pears, pineapples, grapes, etc…

There’s a big difference between starchy-sugary carbs and non-starchy carbs.

Examples of non-starchy carbs: broccoli, cauliflower, carrots, cabbage, lettuce, tomatoes, peppers, celery, eggplant, onions, asparagus, sprouts, lettuce, mushrooms, spinach, zucchini…

Non-starchy carbs are complex fibrous carbs with a skewed volume-to-energy ratio.

Check this out:

- 200g raw broccoli = 68 cals.

- 200g red potatoes = 178 cals.

You can eat three times the amount of broccoli (in volume) as you can potatoes, for the same caloric yield without even factoring out fiber. Chances are, if you go H.A.M. on broccoli, you’re going to hit a substantial point of fullness (or boredom) before you’re able to amass a bunch of energy.

Most non-starchy carbohydrates follow the same trend: They have a low energy yield per their volume and they’re loaded with fiber and other beneficial nutrients. You can eat a lot of them without worrying about amassing excess energetic material.

If you eat lean proteins and non-starchy carbs you will keep your energy consumption to a minimum.

Sort of like how you’ll automatically keep your spending on a leash if you shop at DollarTree instead of Best Buy.

Question:

Are you eating plants and proteins? Specifically lean proteins? Or are you plowing a bunch of energy into your piehole?

third, proteins. one gram

fourth, c and f…

fifth, my system.

sixth, modulate energy

FOR FAT LOSS

conservative.

to minimize muscle loss and undesirable metabolic adaptations, i recommend using a conservative calorie deficit. in general, a conservative calorie deficit is 500 calories below your average daily energy need.

if you’re maintaining your weight, you can assume your energy feed is on par with your energy feed. to reach a conservative deficit, you’d eat 500 fewer calories than you currently are. alternatively, you can calculate a conservative calorie ceiling by multiplying your weight (in pounds) by twelve.

BW [POUNDS] x 12

CONSERVATIVE DEFICIT FOR FAT LOSS

if you weigh 180 pounds and you want to lose fat, then you should eat 2150 calories per day.

math.

upon creating a daily 500 calorie deficit, the numbers suggest you’d lose around one pound of fat per week.

- Sunday: (-500)(-500)

- Monday: (-500)(-1000)

- Tuesday: (-500)(-1500)

- Wednesday: (-500)(-2000)

- Thursday: (-500)(-2500)

- Friday: (-500)(-3000)

- Saturday: (-500)(-3500)

of course, the math isn’t this clean in real life, but this isn’t a bad expectation to have.